The Process of Biocontrol

Biocontrol in weeds can take a range of shapes and forms, from insects that feed on leaves, bore into stems, create galls or make easy entrance for pathogens to attack. Because the challenge to find a suitable biological control for a specific weed can be extremely hard, the roles some play are more subtle such as prevent reinvasion following manual removal or reducing weed spread through reduction in seed or propagule production. Even the reduction of weed biomass can create an opening for the crop or natural vegetation to out compete the weed.

What is success?

Success means different things according to the environment, land use and those that own or manage it. While elimination of the weed is usually preferred, reduction below economic thresholds in farmed situations or to the point where it no longer impacts native ecosystems for environmental weeds, is usually the goal.

In the Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius) biological control program, a weed of national parks in southern states, a reduction to 30% cover was estimated to enough to allow native vegetation to regenerate. By understanding the role and timing of nutrient levels and seasonal flushing of billabongs a successful integrated program for control of the floating fern salvinia (Salvinia molesta) in Kakadu National Park with the weevil Cyrtobagous salviniae was launched.

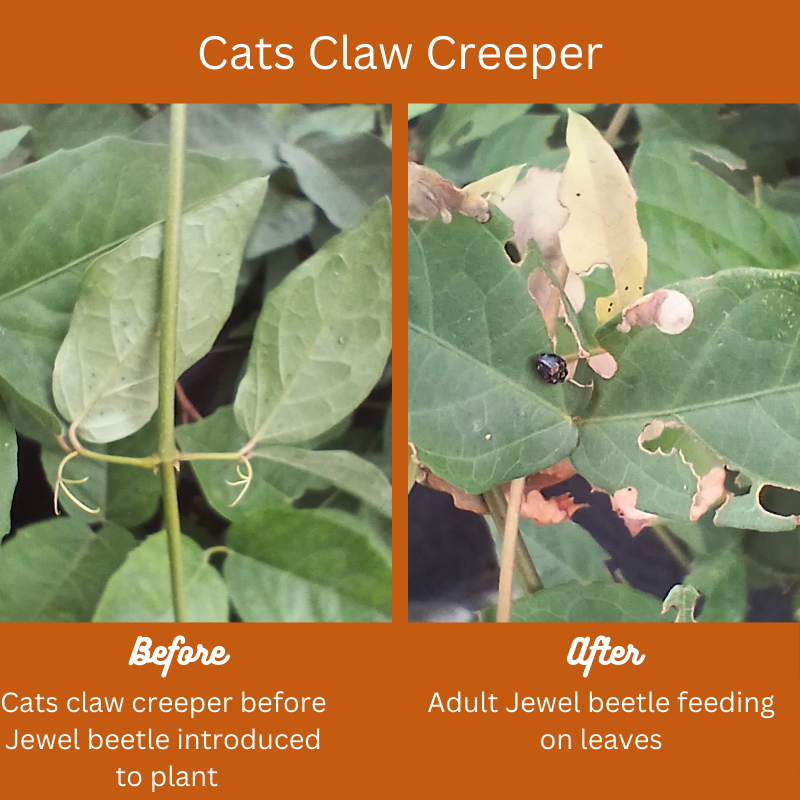

Ecoinsects has been working with land managers and regional groups to release the Cats claw jewel beetle (Hedwigiella jureceki) and a leaf sucking tingid (Carvalhotingis visenda) as part of a broader program to manage Cats Claw creeper (Dolichandra unguis-cati) across South-east Qld. The suppressive nature of these two insects should help allow more conventional management programs to control the weed before it spreads further.

Classic Biocontrol Vs Augmented Biocontrol

Few biocontrols are totally effective in eliminating a weed from the ecosystem, typically they form a balance with their target, that cycles much in the way that prey-predator models operate. Unfortunately, the very limits we use to carefully select new biocontrol agents can be the very limitations to the long-term success of the biocontrol in a region. Selecting insects that are limited to only attacking the weed of choice means that when a local weed population drops to very low levels the insect begins dying out. Weeds can also often adapt to environmental conditions and new areas more readily than the biocontrol. Droughts, floods and bushfires also disrupt the suppression effect of the insect in an area, as their target disappears from the landscape. However, when the drought breaks or the waters recede, the weed often returns, without the insect present.

The introduction of new biocontrol agents for weeds in Australia has usually been highly focused on the early stages: identification, selection and derisking the introduction. Little of the funding is allocated to the distribution and establishment of biocontrol agents, even when they have shown to be successful. We do not make this claim as any sort of criticism of the excellent work being done by research teams around the country, more the lack of industry and government funding being directed to hammering home their good work. We believe that successful management of weeds through the use of biocontrol can only be reliable and have longevity if we move to truly integrate this tool into the integrated weed management systems.

Integration means moving beyond release and move on, to accepting that targeted releases and reintroductions will be needed over years. Ecoinsects is committed to working with land holders and managers to develop effective programs that monitor and manage biological control agents as much as we do the weeds. Where possible combining the timed release of the insects around other management activities in an integrated program.